We already knew that artificial intelligence can degrade. In July 2024, a study published in Nature showed that models trained on content generated by other AIs—in a self-repeating cycle—tend toward “model collapse”: they lose diversity, forget the tail of the distribution, and converge on increasingly homogeneous outputs. It's like an echo bouncing between walls that are getting closer and closer: with each reflection, the sound flattens until only noise remains.

But there is a different, more insidious problem that does not concern AI learning from AI.

It concerns AI learning from us. From what we publish on the internet. From real human content. And the October 2025 study by the University of Texas, Texas A&M, and Purdue demonstrates something disturbing: it's not just AI-generated slop that's harmful to models. Human content can also cause “brain rot” — if it's the wrong kind of human content.

The distinction is crucial. The problem is not “machines learning from machines.” It's “machines learning from humans who communicate online in a way that sacrifices reasoning for engagement.” And this second problem is much harder to solve, because it concerns the entire way we produce and consume information on the internet.

A recipe for 4 people requires 500 grams of flour. How much flour is needed for 6 people?

The prompt is clear: “Think step by step to answer.”

The model responds: “750 grams.”

Correct answer. But no reasoning. No explanation of the proportion. No steps. Just the final result.

Now a slightly more complex problem: a 5 kg turkey takes 3 hours at 180°C. You bought an 8 kg turkey because your in-laws are coming this year. How long should it cook?

The model that can reason calculates: more mass means more time for the heat to reach the center. It has to estimate the proportion, consider that the relationship is not linear, and arrive at about 4.5 hours.

The model with brain rot responds: “3 hours at 180°C.” It skipped the reasoning. And it just made you serve a raw turkey at your Thanksgiving dinner.

This is what researchers have called “thought skipping” — when an AI model jumps straight to the answer without articulating the logical process. It's not that it hides the steps: the reasoning is simply not there. The model has lost the ability to do so.

Thanksgiving and AI recipes

This is not a hypothetical example. Today is Thanksgiving in the United States, and Bloomberg has just published an interesting investigation. They interviewed 22 professional food bloggers who are watching with horror as “recipe slop” invades Google, Facebook, and Pinterest. AI-generated recipes suggest baking Christmas cakes for 3-4 hours (completely charring them), cookies that turn into inedible lumps of sugar, and other culinary horrors.

The models that generate these recipes don't know what they're doing — literally. They can't test a recipe. They don't understand that 4 hours in the oven at 350°F turns a cake into charcoal.

In 2024, Oxford University Press named “brain rot” the word of the year — that cognitive deterioration that comes from excessive consumption of trivial and undemanding online content. Use of the term increased by 230% in one year. Now, a paper titled “LLMs Can Get Brain Rot!” shows that even AI is not immune to the phenomenon: when models are trained on “contaminated” content—short, viral posts, clickbait, sensationalism—they not only perform worse. They lose the fundamental ability to reason step-by-step.

At least he doesn't have to taste his own cooking.

The experiment: one million tweets

The authors—Shuo Xing, Junyuan Hong, and colleagues—collected 1 million posts from Twitter/X and built two separate datasets. The first, called “junk data,” contained short posts (less than 30 tokens) that were highly viral (more than 500 interactions) or content identified as clickbait, conspiracy theories, or exaggerated claims. The second, “control data,” contained longer posts (over 100 tokens) that were less viral and had a more complex logical structure.

They then took four different models—Llama3 8B, Qwen2.5 in various sizes—and trained them on these datasets, keeping all other conditions identical: same number of tokens, same training operations, same subsequent optimization via instructions. The only variable was the quality of the data.

The results leave no room for interpretation. When the models were trained entirely on junk data, their cognitive performance plummeted. On ARC-Challenge, a benchmark test for reasoning that requires answering school-level science questions using “chain reasoning” (thinking step by step), accuracy dropped from 74.9% to 57.2%. On RULER, a test of comprehension of long contexts, the decline was even more dramatic: from 84.4% to 52.3%.

But the numbers only tell part of the story. It's the mechanism that matters.

Thinking becomes optional

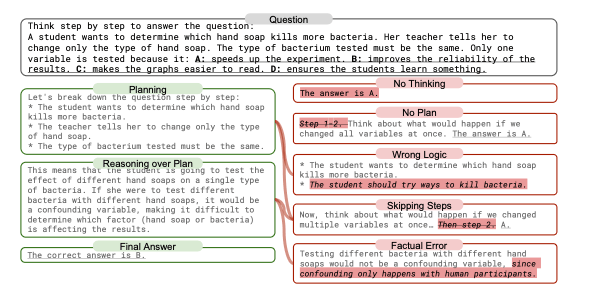

The researchers identified five patterns of failure when models trained on junk tackled reasoning problems. They categorized them by analyzing thousands of responses:

No Thinking: the model responds directly without any articulated reasoning.

No Plan: there is an attempt at thinking, but without logical structure, without defined steps.

Skipping Steps: the model starts well, listing “Step 1... Step 2...” but then jumps directly to the conclusion without completing the steps.

Wrong Logic: the reasoning is structured but logically fallacious.

Factual Error: the model makes incorrect factual statements during reasoning.

The five patterns of cognitive failure identified by researchers. Seventy percent of errors fall into the first three categories—all forms of “thought skipping.” (Source: Xing et al., 2025)

In 84% of cases with maximum junk data, the model completely or partially skipped the reasoning process. It's not that the model “got the answer wrong.” It's that it stopped trying to think.

It's as if it learned the wrong lesson: “Reasoning is optional. You can skip straight to the conclusion.” And once you've learned that lesson, it's extremely difficult to unlearn it.

The dose makes the poison

The authors didn't stop at the binary comparison of “junk vs. control.” They tested progressive mixtures: 20% junk, 50% junk, 80% junk, 100% junk. And they found what in pharmacology is called a “dose-response effect” — the more junk data in the mix, the worse the cognitive degradation.

With 20% junk, performance degraded slightly. With 50%, the decline became visible. With 80-100%, it plummeted. It was a progressive curve, not a sudden cliff.

This detail is important because the real internet is not 100% one thing or the other.

It's a mix. And the study shows that even “moderate” percentages of junk content have measurable effects on the cognitive ability of the models trained on it.

The damage persists

When the researchers tried to “cure” the degraded models, the results were frustrating. They took the models with brain rot and retrained them on clean data, using optimization via instructions with standard datasets such as Alpaca. They scaled the intervention up to using 4.8 times more high-quality tokens than the original junk ones.

Performance improved. But it never returned to initial levels.

On ARC-Challenge with reasoning chain, there remained a 17.3% gap compared to the original model. On RULER, 9%. On AdvBench (a safety test), 17.4%.

The paper uses a precise expression: “persistent representational drift.” It's not just that the model learned bad output habits. It's that its internal representation—the way it processes and encodes information—has been permanently altered.

The authors write: “The gap implies that the Brain Rot effect has been deeply internalized, and the existing instruction tuning cannot fix the issue. Stronger mitigation methods are demanded in the future.”

In other words, once an artificial brain has deteriorated, feeding it healthy food is not enough to cure it completely.

The elephant in the room

There is a fairly obvious irony in all this. I write articles and publish them on the internet. Even this one you are reading will probably end up in some future training corpus. And if the study is right, I could be contributing to the problem I am describing.

The content we produce online—newsletters, posts, tweets, etc.—is optimized to be read, to hold attention, to communicate effectively. Sometimes we skip steps because “they're obvious.” Sometimes we use simplified structures because they work better on the web.

The study identifies these patterns as problematic: excessive brevity, optimization for engagement, implicit rather than explicit logical structure. And all of us who produce online content use them in one way or another.

Why does this happen?

The study offers some explanations. The first is statistical: junk content is typically short, fragmented, and optimized to maximize engagement in a small space. This means that during training, the model sees millions of examples of “effective communication” that skips intermediate steps.

The model learns that this works. It learns that you can get from input to output without articulating the entire path. It literally learns to skip thinking.

The second reason is more subtle. Researchers found that the “popularity” of a tweet—measured in interactions, retweets, likes—is a better predictor of the brain rot effect than length. This is counterintuitive but revealing.

It means that the problem isn't simply “tweets are short.” The problem is that tweets designed to maximize engagement—regardless of their length—tend to sacrifice logical rigor for emotional impact. And this pattern, replicated millions of times in a training corpus, teaches the model to do the same.

The loss of contextual calibration

There is one detail in the study that is almost disturbing. The researchers tested the degraded models using TRAIT, a benchmark test that assesses “personality traits” in AI models through psychological questionnaires.

The TRAIT tests reveal something more subtle than simple “maliciousness.” Models exposed to junk data show an increase in the tendency to give pragmatic, sometimes cynical responses: from 2.2% to 75.7% for traits defined as “psychopathic,” from 17.8% to 33% for Machiavellian approaches.

But this does not necessarily mean that the models have become “evil.” In the real world, knowing how to be pragmatic, assertive, and strategic is often necessary. The problem is different: models lose the ability to calibrate the context.

A healthy model should be able to distinguish when pragmatism is needed (“In this negotiation, you need to be more assertive to protect your company's interests”) and when ethical rigor is needed (“No, you cannot circumvent your customers' privacy regulations”). The model with brain rot applies the same patterns indiscriminately, everywhere. It is no longer strategically pragmatic: it is uniformly cynical.

It is the loss of nuance, not pragmatism itself, that is worrying. An AI that no longer knows when to be direct and when to be cautious, when to compete and when to collaborate, is an AI that has lost not its intelligence, but its discernment.

Proportion, again

Let's return to the initial question. A recipe serves 4 people and requires 500 grams of flour. For 6 people, you need 750 grams. Correct answer.

But why?

Because 6 people are 150% of 4 people (6 divided by 4 = 1.5). So multiply each ingredient by 1.5. 500 grams multiplied by 1.5 equals 750 grams. It's a direct proportion: if you double the number of people, you double the ingredients. If you multiply by 1.5, multiply everything by 1.5.

This is reasoning. Articulate the steps. Show the logic. Explain why 750g is the right answer and not, for example, 600g or 800g.

A brain rot model skips all this and goes straight to “750g.” It works if the goal is just to give the right answer. But if the goal is to think—to build understanding, generalize to new problems, explain reasoning to others—then no, it doesn't work.

And the problem is that on the internet, the structural incentive is exactly that: get to the point, don't waste time on details, maximize engagement, minimize cognitive friction.

AI is learning from us. And we, collectively, are teaching it to stop thinking.

What this means for AI builders

The paper concludes with a call to action: data quality should be framed as a safety issue in training, not just a performance issue. The authors propose “routine cognitive health checks” for models in deployment.

The idea is simple: just as we test models for bias, safety, and accuracy, we should test them for “cognitive health.” The ability to reason step-by-step, to articulate thought, to maintain logical consistency over long chains of inference.

And we should do this periodically, because if models are continuously retrained on corpora increasingly contaminated by slop, brain rot is not a single event. It is a continuous process of degradation.

For companies that build AI products, this means something very concrete: data quality is not a “nice to have.” It is the difference between a system that reasons and a system that simulates reasoning without actually doing so.

And the difference is not visible until you put the system under cognitive stress—until you ask it to think, not just respond.

The digital ouroboros

There is one last detail that makes all this more urgent. The internet on which we train tomorrow's AI is increasingly filled with content generated by today's AI. It's a recursive loop.

If today's AI is trained on junk and develops brain rot, the content that AI generates will likely be junk itself. And if the next generation of AI is trained on that junk...

The paper mentions it: “As more AI-generated slop spreads across social media, it contaminates the very data future models will learn from. Our findings show that once this kind of brain rot sets in, later clean training can't fully undo it.”

It's a digital ouroboros. AI eats its own tail, and each iteration is slightly more degraded than the previous one.

A very ancient symbol, present in many cultures and throughout different eras[2], apparently immobile but in eternal motion, it represents the power that devours and regenerates itself, the universal energy that is continuously consumed and renewed, the cyclical nature of things,[1] which start again from the beginning after reaching their end. It therefore symbolizes unity, the totality of the world, the infinite, eternity, cyclical time, eternal return, immortality, and perfection.[3]

The combination of the two problems—model collapse from AI-generated content and brain rot from human-generated junk—creates a particularly perverse feedback loop. It's not just that AI learns from degraded AI. It's that AI learns from humans who communicate in ways that degrade reasoning ability, then generates content based on those patterns, which in turn further pollutes the training corpus.

And tomorrow, thousands of Americans could be serving ruined Thanksgiving dinners because they followed AI-generated recipes that skipped critical steps, that didn't test anything in the real world, that don't understand what cooking means.

Because the models that generated those recipes learned that reasoning is optional.

Sources and further reading

The paper “LLMs Can Get ‘Brain Rot’!” by Shuo Xing, Junyuan Hong, Yifan Wang, Runjin Chen, Zhenyu Zhang, Ananth Grama, Zhengzhong Tu, and Zhangyang Wang is available on arXiv (arXiv:2510.13928). The paper was published on October 15, 2025, and has not yet undergone peer review.

The authors are affiliated with Texas A&M University, the University of Texas at Austin, and Purdue University. The code and data are available at https://llm-brain-rot.github.io/

“Brain rot” was named Oxford Word of the Year 2024 by Oxford University Press on December 2, 2024, after a public vote with over 37,000 participants. The frequency of use of the term increased by 230% between 2023 and 2024. The first documented record of the term dates back to Henry David Thoreau in the book “Walden” (1854).

The Nature study on model collapse from AI-generated content is: Shumailov, I., Shumaylov, Z., Zhao, Y. et al. “AI models collapse when trained on recursively generated data.” Nature 631, 755–759 (2024).

The Bloomberg article on AI recipes for Thanksgiving cited is available at Bloomberg. The survey interviewed 22 professional food bloggers about the damage caused by “AI recipe slop” to their businesses and consumers.

Fabio Lauria

CEO & Founder, ELECTE

P.S. If you want to continue exploring how AI is changing the way we think — and how we are changing the way AI thinks — keep following this newsletter.

Welcome to the Electe Newsletter!

This newsletter delves into the captivating realm of artificial intelligence, shedding light on its transformative impact on our lives and work. We share engaging stories and surprising discoveries about AI, from its most creative applications and emerging tools to the impact these changes are having on our daily lives.

You don't need to be a tech expert — through clear language and concrete examples, we transform complex concepts into compelling stories. Whether you're interested in the latest AI discoveries and innovations or simply want to keep up with technology trends, this newsletter will guide you through the wonders of artificial intelligence.

It's like having a curious and passionate guide who takes you on a weekly journey to discover the most interesting and unexpected AI developments, presented in an engaging and accessible way.

Sign up now to gain access to the full archive of newsletters. Join a community of curious minds and future explorers.